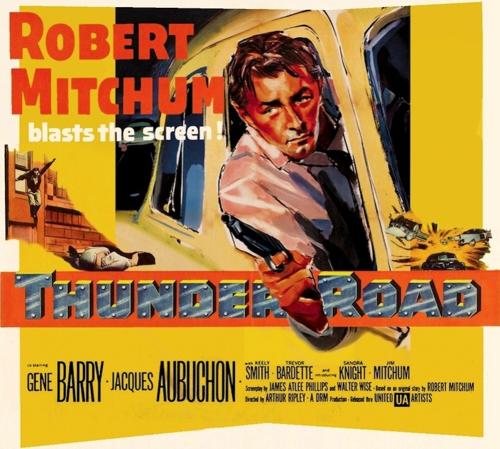

“On the first of April, Nineteen-Fifty-Four, the federal man sent word he’d better make his run no more.” These are lyrics from the song from the 1958 Movie “Thunder Road,” a fictional story written by Robert Mitchum but based on actual Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms records.

Thunder Road was code name for a moonshine route that ran from Harlan, Kentucky, into Knoxville through Maynardville, to the truck route Papermill Road and onto Kingston Pike. The story dealt with a mountain boy that ran ‘shine on this route and allegedly ended up losing his life in a crash right outside of Bearden. According to legend, 20 years after prohibition, “the devil got the moonshine and the mountain boy that day.”

John Burgess Fitzgerald Jr.

Many area authors have written of the legend of Thunder Road: Kate Clabough, Alex Gabbard, Jack Neely, Brooks Clark, Fred Brown, Jack Rentfro and many others. Ironically, through all of their research, no one, including the writer, could find written documentation of the account in historical records and newspapers.

The late John Fitzgerald Jr., graduate of Farragut High School, class of 1956, however, was one fella that, by his account, was an eyewitness. He adamantly maintained his story until he left this world in 2005. According to John, he and some friends had ridden their bicycles to Galyon’s Service center for a soft drink. Upon their arrival, they noticed some men in suits that seemed to be in a frenzy about something.

The men tried to shoo him from what they were doing but he moved to an adjoining property belonging to his father and observed as they parked their vehicles along a row of trees from the side of the road and proceeded to put up a road block. He watched as the driver of a 1952 misty green Ford ran the roadblock and fatally ended up in a Lenoir City Utilities Board substation, spilling moonshine in the area of the wreckage.

Young Fitzgerald remarked that he thought what a waste of the young man’s life, and that he had heard his name was Tweedle-o-Twill.

As with any legend and storytelling tradition, the yarn changes with the years and in direct proportion to the number of people spinning it. Perhaps in this case, it might be interesting to see if one could validate the story as told by Fitzgerald.

In 1954, young John would have been 16 years old. He was living in the Bluegrass community of Concord and a trip from his home to Morrell Road was a little more than two miles.

Apparently Galyon’s service center did not cater to much advertising; however, a Knoxville City Directory listed that a John D. Galyon was owner of Cottage Terrace Tourist Court which was in Bearden on Kingston Pike. Locals familiar with the Bearden area report that the same Galyon that owned the service center also owned an adjacent tourist court. A lawsuit in 1961 relates that J.D. Galyon and sons were awarded $42,600 in settlement for property at the corner of Kingston Pike and Vanosdale Road to be used in the building of Interstate 40. Of interest, at that time, Vanosdale Road intersected directly with Kingston Pike. Today it is diverted by Buckingham Drive. Research also notes that there were two Galyon brothers who ran service centers during that time as well but their establishment was on Chapman Highway.

Mr. Fitzgerald’s father was involved in several real estate developments with Oliver Smith Jr. who, coincidentally, was one of the developers of West Town Mall at Morrell Road. When John Jr. mentioned stepping onto his father’s land, it is quite possible that his father was at least part land owner of the property later to become West Town Mall.

Inquiries with Mr. Shannon Littleton of LCUB have confirmed that LCUB did service the Deane Hill and Rocky Hill area during the 1950s.

As it seems, John Fitzgerald Jr.’s account of the Thunder Road incident is fairly well authenticated. The writer eagerly awaits the release of the 1950 census in 2022 to confirm additional property lines and ownership.

But it remains, who was Tweedle-o-Twill? Could his name have been “Tweedle”, e.g.; Tweedle O. Twill or O’Twill? Other names have been offered as possibilities for the mountain boy, but, one by one, they have not proved to be probable candidates because they were either in prison or lived long past the day of the fatal crash.

The final question is: did this actually happen, was this a “fig newton” of John Fitzgerald’s imagination or perhaps … APRIL FOOL!

Mona Isbell Smith is a retired computer systems analyst who enjoys freelancing.