I admit I was always envious of my brother and the other boys of the Fork, because they were allowed to freely roam the fields and woods, often under the guise of hunting or fishing. As an adult, my brother continued to share with me photos of the interesting places he had explored in the Fork, the lands between the French Broad and Holston Rivers all the way to the Jefferson and Sevier County lines. He first introduced me to the Sheep Cave through his old photos, though at that point I didn’t know it had a name.

As an educator, I believe in experiential learning, and I love to physically immerse myself in whatever I’m researching, which is why I bought chest waders to venture into the wetlands of Swan Pond to experience daybreak as it came to life. It’s how I have worn out hiking boots in the woods tracking down overgrown cemeteries and old home sites. And it’s the reason I was accompanied by friends with better footing, quicker reflexes and a stronger grip when I descended down the bluff at Paint Rock.

It’s also why I was determined to experience the Sheep Cave for myself. My brother passed a few years ago, but last year, Fork resident Ronnie Stiles said he knew where it was because he used to play there as a kid. With permission from the land owner, he was my ticket in.

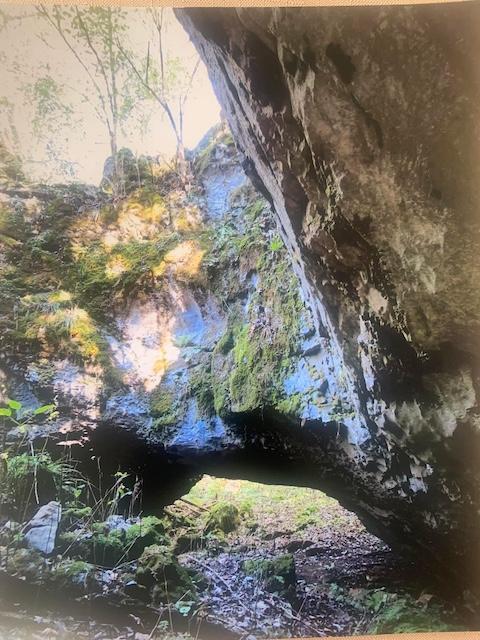

The Sheep Cave appears to be part of a collapsed cavern, where the rim is about 25-feet tall. The rim is edged by two natural arches, while the two caves have multiple passage ways and include a “blue hole” of swirling waters that disappear into the depths. The stream that feeds the blue hole originates from somewhere beyond the visible distance in one cave, while another portion of the cave empties the stream into the French Broad. I’ve been to the stream’s mouth at the river, but I have no idea what lies between the two. The cave does have stalagmites and stalactites, and besides “the tree in the hole,” what is now the floor is covered in yellow trout lilies.

hole,” what is now the floor is covered in yellow trout lilies.

Local Fork lore says that the Sheep Cave got its name because it’s where farmers along the river pastureland hid their sheep during the Civil War so that troops searching for food supplies wouldn’t get them. As evidenced by the Boy Scout article and other articles from the 1930s that tell of fox hunts, it and its springs that furnished fresh water to the community were once familiar to area residents.

For the kids who knew about it, it was a great place to play back in the day. Now, it’s just one more interesting place that’s been forgotten in the Fork.

- The Sheep Cave rim and arch by author’s brother

- The mouth of the Sheep Cave on the French Broad

- The Sheep Cave rim and arch by the author’s brother

- The author’s guide at the Sheep Cave entrance

- Sheep Cave rim

- The Sheep Cave rim and arch by author’s brother

Jan Loveday Dickens is an educator, historian and author of Forgotten in the Fork, a book about the Knox County lands between the French Broad and Holston Rivers, obtainable by emailing ForgottenInTheFork@gmail.com.

Was a great day… Brought back alot of good memories.. thanks for your curiosity ❣️❣️

Thank YOU, Ronnie! It wouldn’t have happened without you!

Thank you for this enlightening article. East Tennessee is a cornucopia of interesting geological features

Ballinger! I learned about him while teaching at C-N! Fascinating man.

Great article there’s definitely a lot of areas in Knox, Jefferson and Decide counties that’s been forgotten. But needs to be remembered article reminds me of the man who lived in a cave for years.