One of my ancestors is Isaac Jonathan Newman, one of my 6th great grandfathers, eight generations back. His descendants are legion, so I am but one among thousands.

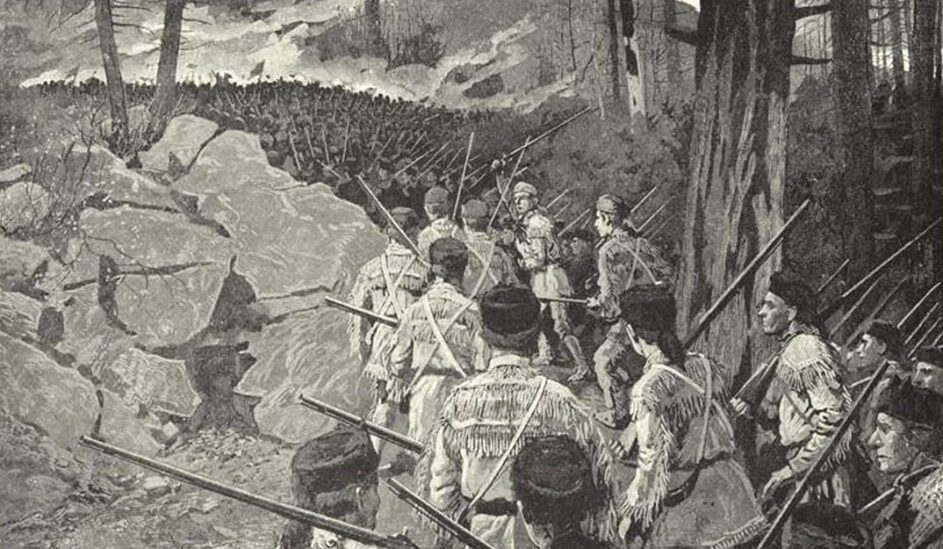

Newman was born in May of 1755 in Guilford County, North Carolina. In October of his 25th year, he was fighting at the Battle of King’s Mountain in South Carolina during the American Revolution. By 1792, he and his bride, Sarah Irwin, and their children were living in Jefferson County at Dumplin Creek, officially taking possession of land grants as payment for his services during the war in 1797. Isaac and Sarah had seven children, six sons and one daughter, notable among them was their son Samuel, one of the founders of Mossy Creek Baptist College that later became Carson-Newman.

Newman’s life trajectory was not unlike many of the Overmountain Men who journeyed to what became Tennessee after the Revolution: they took possession of their land grants, became farmers and merchants, and, in a most unseemly fashion after fighting for “freedom,” jumped right into the practice of keeping others in human bondage.

Sometime after 1820, he and Sarah moved to McMinn County and settled in the area near what is now Zion Baptist Church (where he and Sarah are both buried). In 1830, their only daughter, Rebecca Stephenson (my 5th great grandmother), died, and they had already lost one son.

What I personally found fascinating about Isaac was his Last Will and Testament and how hard some of his heirs fought to overturn his wishes. By 1832, Isaac’s age and declining health were catching up with him. Whether it was the influence of one of his children, the growing manumission movement in East Tennessee, or knowing he was about to meet his maker, and it was time to make amends, I do not know, but Isaac decided to free the people he had enslaved after his death:

“…as for my Negroes, I do emancipate them all after the following manner: All that is now over 25 years of age shall serve those they are now living with till the first day of February next, and those that is under 25 years shall be disposed of in the following manner, to wit: my Negro child, Peter, 4 years old shall serve my son Joseph till he is twenty five years old and be taught to read the English language correctly: my Negro man, Anthony, born the twenty eighth of August, 1811, shall serve my son Jared till he is twenty five years old: my Negro woman, Betsy, two children Daphney and Peter, shall serve my son Samuel till they are 25 years old and be taught to read the English language correctly: my Negro woman Fanny, 2 children Charles and Lewis shall serve my son Isaac till they are 25 years old and be taught to read the English language correctly: my Negro girl Priscilla shall serve my son Joshua till she is twenty five years old, being now 18 years old: my Negro man Gan born February 28th 1819, shall serve my son Robert till they are twenty five years of age: and my Negro girl Matilda born December thirtieth 1817, shall serve my granddaughter Elizabeth Cate till she is twenty five years of age and taught to read correctly. None of the above mentioned Negroes is to be transferred out of my own family or to be removed out of the counties of McMinn, Monroe or Jefferson: And if any of the females should have children before they are twenty five years old, their children shall be born free.”

To modern sensibilities, it’s easy to read this and think, just let them go, shouldn’t have been doing that in the first place. But at the time, that was easier said than done. Old Isaac wanted to be sure they had the skills necessary to navigate a landscape that was overall hostile to their emancipation.

The Tennessee legislature had done everything to make it next to impossible to free the enslaved. By the time of Isaac’s death in January 1832, all free Black people were supposed to remove themselves from the state, with emigration to Liberia as one of their options. They had to petition the court to remain in the place they called home.

In fact, one of those named above, Gan (also referred to as Cam), had to petition for his freedom, which should have occurred in 1844. Isaac’s son Robert had sent him to live with Elizabeth Stephenson Cate (Rebecca’s daughter) and her husband, Gideon Cate (grandson of John Cate Sr. of Dumplin Valley). It seems Gideon was less than enthusiastic about affording Gan the liberty he was promised. It took Gan two runs at the courts to make it happen, but on October 6, 1851, Isaac’s word was made true.

I look at the names of those Isaac intended to liberate, and I wonder how many of them made it to freedom. I do not know if Peter, for example, was Isaac’s biological child or he was simply referring to him in the possessive. What name did each of them take upon gaining their freedom, if they did? Did they stay in Tennessee or strike out for the west or head north? Whose ancestors are they, and who is looking for them, now?

Any Black person in America descended from the enslaved mostly runs into erasure four to five generations back. But I can sit and run my lineage back to Plantagenet kings, Irish clans, Charlemagne and Byzantine emperors. It would be disingenuous, at best, not to recognize that there is privilege in that alone.

Beth Kinnane is the community news editor for KnoxTNToday.com