Contrary to public opinion, Tennessee athletics sometimes gets something right.

Recognizing football Trailblazers is a fine idea. Some already see it as making up for lost time. OK, there are a few raised eyebrows. Cynics are calling it just another recruiting ploy.

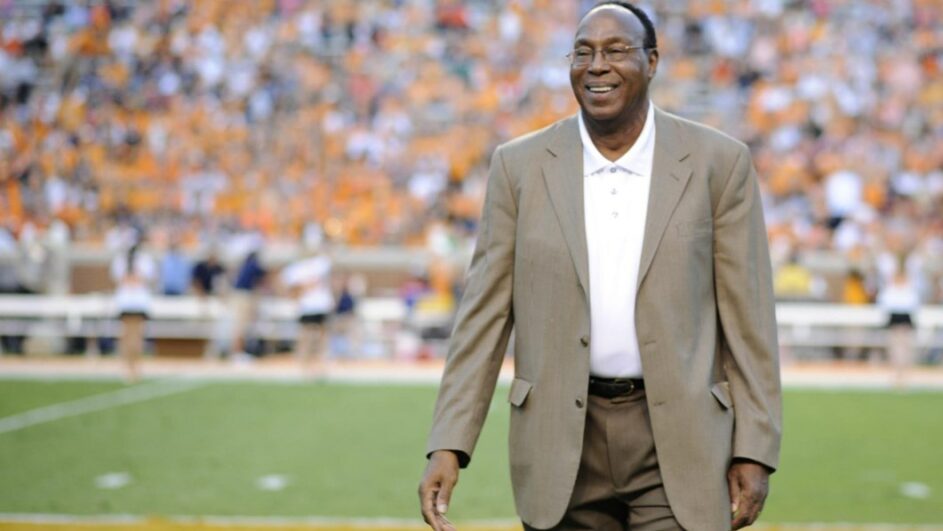

If you are spending a bundle for larger-than-life bronze statues, Lester McClain, Jackie Walker, Condredge Holloway and Tee Martin are deserving. The four required no revision of history. They were first in several ways.

It seems deeply symbolic that they are to be placed near a famous doorway to Neyland Stadium. Indeed, Lester opened the door for Black players to be Volunteers. The wingback/receiver was a perfect match for the challenge.

Jackie was Tennessee’s first Black all-American, an excellent linebacker who broke out of the shadow of Steve Kiner and Jack Reynolds and achieved greatness on his own. Five times he returned interceptions for touchdowns.

Condredge was truly the original Artful Dodger, a quarterback magician, ticket salesman and a great story, first-round draft choice as a shortstop and even better in basketball and ping-pong.

It sounds strange to say Tee did what Peyton Manning didn’t, direct an undefeated, national championship team. Al Wilson had a little something to do with 13-0. He may have been first to dent helmets. It would have been OK to have five honorees. Come to think of it, there are other firsts.

A quirky set of circumstances turned Lester McClain into the first Black Vol. He was supposed to be second, just a convenient roommate for the far more famous Albert Davis.

Whoa Nelly, as Keith Jackson used to say, Davis was a good enough running back to knock down the segregation wall.

What follows is how Albert Davis missed becoming a Vol.

On Friday the 13th in September 1963, Albert made his first appearance on behalf of Alcoa High, at Everett. He was a freshman, a year older than most, 6-1 and 218. Tensions were high but there were no disruptions. Three levels of police plus the FBI made a point of being obvious to fans.

Davis turned his first carry into a 40-yard touchdown run. That was his only play of the game. Alcoa won easily. The crowd went away wondering what was to come.

What came was a spectacular career, prep all-American honors, more than a hundred scholarship offers, even one from a school in the Southeastern Conference.

Chuck Rohe, Vol track coach and football recruiter, was a decisive advocate for integration. President Andy Holt agreed it was time. If Doug Dickey was reluctant, it didn’t show. Going for Albert Davis was automatic.

“Albert, without a doubt, was the most outstanding football player in Tennessee for a number of years,” Dickey said much later.

Recruiting Davis was no easy sell. He was thinking he might be better off elsewhere. Dickey appeared at “Albert Davis Day” at Alcoa in April 1967, stepped to the microphone and led the crowd in a rousing cheer, “We want Albert! We want Albert!”

A few days later Albert signed. The newspaper headline emphasized “first Negro athlete.” Credit Tennessee fans with drowning out the few protests.

Too soon the cheering stopped. The national college entrance testing service received an anonymous phone call. Someone claimed someone else had taken the qualifying test for Davis.

Dickey said Davis had been academically certified by the NCAA and the SEC.

Investigators were dispatched. Davis was asked to submit a signature for comparison. When he refused – out of principle, he said – Tennessee pulled the scholarship offer. Dickey declined to comment.

“I really don’t think it would be appropriate. The public record is the public record, and I think I’ll leave it at that.”

Lester McClain was stuck. There was no “roommate” assignment to fulfill. There were whispers that Tennessee might withdraw another scholarship.

Bill Garrett, Nashville pharmacist, UT alum, donor and first to recommend McClain to the Vols, made another recommendation: Tennessee must keep its word to Lester McClain.

It did.

Quarterback Jim Maxwell became Lester’s first roommate. Of course, he was white. White quarterback John Rippetoe was next. Instead of problems, deep friendships emerged. Lester was so easy to like – and respect. What’s more, he could play.

Albert Davis was said to be very unhappy. He signed with Michigan State. He supposedly took the entrance exam again and scored two points higher. He landed at Tennessee State.

There was a time he wanted out. He thought he was transferring to Houston. No one met his flight. He returned to Nashville.

In 1971, Davis went in the 11th round of the NFL draft to the Philadelphia Eagles. Nothing happened. To the best of my knowledge, that was the end of Albert football.

He became a student. He said he had not previously been one. He said he actually repeated ninth grade at Alcoa. Eventually, he earned four degrees, including a doctorate. He retired as a high school principal in Camden, New Jersey.

Do you suppose Albert might be getting Lester’s statue at the University of Tennessee if he had made it there?

Marvin West welcomes comments or questions from readers. His address is marvinwest75@gmail.com.