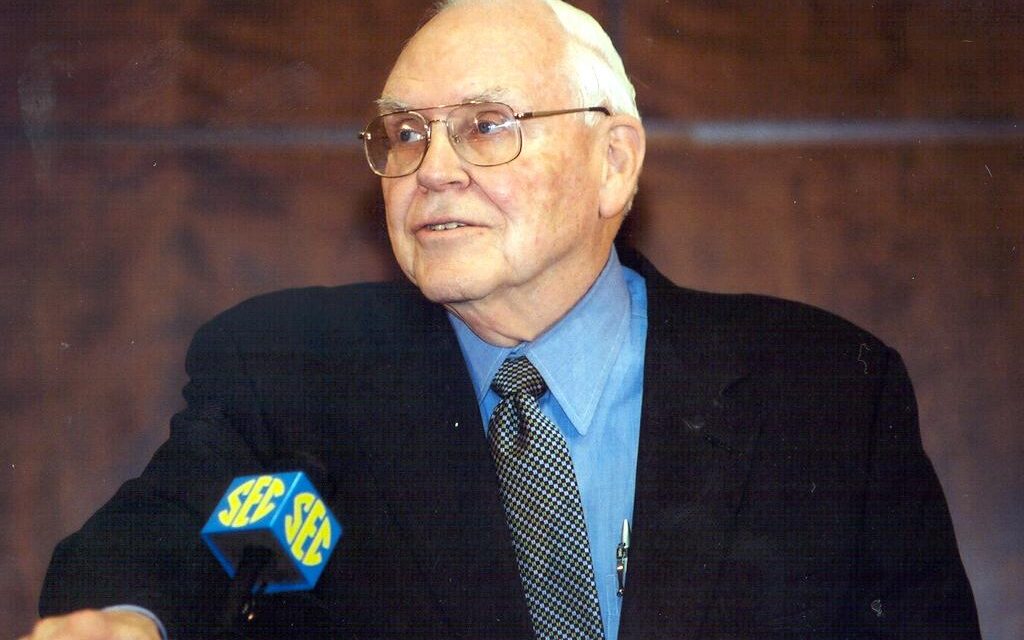

Roy Kramer did not invent college football. He did make it better. If there was an official Mount Rushmore of the game, he might be up there with Nick Saban and Herschel Walker.

Kramer, outstanding as commissioner of the Southeastern Conference, became one of the most powerful leaders in college sports. Long before that, he was the greatest coach in Central Michigan University’s history (83-32-2). There was one scar on his record. He once served as athletics director at Vanderbilt.

I used to tease him about how smart he was to have moved on.

Roy, 96, died December 4, 2025. A celebration of his life will be held at 11 on Thursday at First United Methodist Church in Maryville. A Friday graveside service at Grandview Cemetery will begin at 9. The full obituary is here.

Kramer, born in Maryville, played football and graduated from Maryville College. He was an officer in the U.S. Army during the Korean conflict. He and former classmate Sara Jo Emert married in 1951. In retirement, they returned near enough to their roots, Tellico Lake.

Roy earned a master’s degree from Michigan. He was coach of three Michigan high school state championship teams. At Central Michigan, he won an NCAA Division II national championship and was named national coach of the year.

Despite his 12-year connection to Vanderbilt, he was chosen in 1990 to lead the SEC. I thought he was brilliant.

He was a calm commissioner but his influence resonated nationwide. The SEC added South Carolina and Arkansas, created divisions and launched a league championship game. It was a TV gold mine.

Kramer was also architect and founding chair of the Bowl Championship Series, which for 16 years determined the national champion. That was the groundwork for the modern playoff system.

In his spare time, he negotiated a ground-breaking multi-sport national broadcast agreement with CBS. That set the standard for conferences all over the country. In Kramer’s last year on the job, the SEC distributed $95.7 million to its 12 schools.

Former Big East commissioner Mike Tranghese said a lot in one sentence: “By any standard, Roy’s influence was mind-boggling.”

Through all this, Roy’s priority was said to be the welfare of college athletes. Somebody found a way to say thank you. The SEC Athlete of The Year Award is named for Roy Foster Kramer.

Current SEC commissioner Greg Sankey summed it up far better than I can.

“Roy Kramer will be remembered for his resolve through challenging times, his willingness to innovate in an industry driven by tradition, and his unwavering belief in the value of student-athletes and education.

“His legacy is not merely in championships or commissioner’s decisions, but in a lifetime devoted to lifting student-athletes and believing in the power of sport to shape the lives of young people … the foundations he built, on campuses within the SEC and across college sports, will resonate for generations to come.”

Some of Kramer’s work was criticized, mostly by schools that didn’t make the playoffs.

“We’ve been blamed for everything from El Nino to terrorist attacks,” he said at a retirement dinner. He smiled.

I never was a critic. I applauded his football speech to the National Football Foundation’s East Tennessee chapter after he received the Robert R. Neyland Award.

“The game teaches so many things. The lessons of toughness, discipline, striving for excellence, teamwork, are taught far better on a football field than in any classroom at any level.

“In what other laboratory can one experience a Polish right guard and an Italian center opening a hole for an African-American running back to score a touchdown and achieve the ultimate goal of victory?”

Kramer said he was greatly concerned about the great game, not at Neyland Stadium or in Tuscaloosa or Ann Arbor, Michigan.

“I’m concerned that it survives on the more than 650 college campuses where teams will never play on television, where they will play in stadiums that seat probably less than 10,000.

“Far more importantly, I’m concerned about Friday nights, that the game survives on dusty fields up in the hills of East Tennessee, on the muddy surfaces of our cities, on the gritty plains of the Midwest.

“I thoroughly understand concerns about health issues in the game today, but unless you’re in a prone position on your couch, there aren’t many places in life where you don’t have to take risks, and they certainly are less on a high school playing field than a 16-year-old driving a car around Knoxville.

“This great nation was not built on softness or avoiding risks. This nation was built on dreams.”

Marvin West welcomes comments or questions from readers. His address is marvinwest75@gmail.com