Knoxville has produced a number of notable figures throughout its 200-year-plus history. South Knoxville has had its share. But one of its most outstanding native sons is probably known the least, although his name lives on in our ever-burgeoning Urban Wilderness.

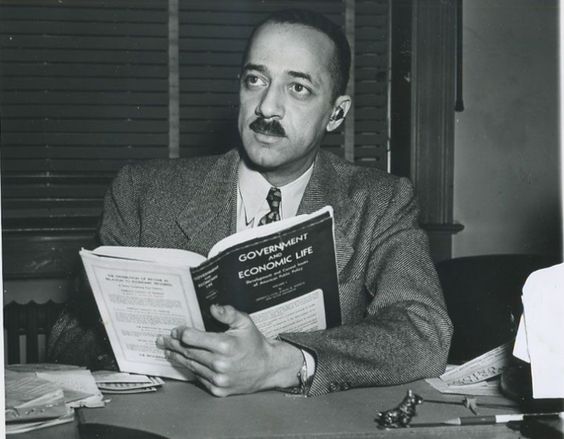

William Henry Hastie was born in Knoxville and spent his first 12 years here, though his parents were from Alabama and Ohio, originally. He grew up in a house still standing off Moody Avenue and went on to become the country’s first Black federal judge and governor.

His hometown eventually honored him by naming a park not far from his childhood home the William Hastie Natural Area.

According to Gilbert Ware’s biography, “William Hastie: Grace Under Pressure,” Hastie’s mother, Roberta Childs, was born in 1867 in Marion, Ala. One of her ancestors had been an African princess who was sailing to France to go to convent school in 1794 when her ship was overrun by English privateers who captured her and sold her into slavery in Philadelphia. Roberta attended Lincoln Normal School and finished her education at Fisk University and Talladega College before becoming a teacher in Chattanooga.

Hastie’s father, the second William Henry Hastie, was born in Ohio, where his father and grandmother had moved after she managed to buy their freedom from their owner in Mobile, Ala. Hastie’s dad went to Ohio Wesleyan Academy and Howard University, where he studied mathematics and pharmacy, respectively. Unable to get a job in either field, he ended up becoming the first Black ever appointed as a clerk for the U.S. Pension Office. He met and married Roberta Childs in Chattanooga.

The third William Henry Hastie was born Nov. 17, 1904, in Knoxville. An only child, he received consistent training from his parents, especially his mother, to fight racism. In her late 30s when Hastie was born, Roberta retired from teaching to devote herself to her son’s education in academics and life.

The Hasties lived in South Knoxville, in a two-story house off Moody Avenue. Ware says that Blacks and whites lived in the same neighborhood, and though they did not socialize, their children played together. Young Hastie made it clear to his white playmates that he would not tolerate being called the “n” word, and they treated him with respect.

Regarded by his peers as a bookworm, Hastie was enough of a normal boy to play pranks and get into trouble. His parents would punish him accordingly, and he learned valuable lessons about honesty and discipline.

In 1916, the elder Hastie was transferred to Washington, D.C., and William finished his last two years of grammar school at Garnet Elementary School. He then went to Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School, an exceptional school where he was in college preparatory classes.

His father died during his senior year, but Hastie finished strong and became valedictorian. He went on to Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he and his Black friends experienced subtle and overt racism. He was an outstanding runner but wasn’t allowed to dine in restaurants after a team win. He also was an outstanding student, winning numerous academic awards.

In 1925, Hastie was offered a graduate fellowship to either Oxford University or the University of Paris, but he wanted to do his graduate work in the United States. He took a faculty position at a boarding high school in Bordenton, N.J., to save money to attend Harvard Law School, which he entered in 1927. He became an editor for the Harvard Law Review in his second year and went on to earn his doctorate in juridical science.

Hastie had a remarkable career as a lawyer, breaking down barriers for Blacks and inspiring generations. He worked in private practice from 1930 to 1933 in D.C. and was dean of the Howard University School of Law (1939-46). He also was exceptional in his career in government, serving in the Department of the Interior (1933-37) and as a civilian aide in the War Department (1940-42), in addition to becoming the first Black federal judge (1937-39) and first Black territorial governor (1946-49) of the U.S. Virgin Islands.

He also became a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, serving from Oct. 1, 1949, to May 31, 1971, and as senior judge from May 31, 1971 till his death on April 14, 1976.

Hastie may not be known as an outdoorsman, but South Knoxville is lucky to have a patch of wilderness honoring his legacy and possibly inspiring youngsters to set goals as lofty as his.

Betsy Pickle is a freelance writer and editor who particularly enjoys spotlighting South Knoxville.