Originally published September 15, 2017.

One of the great revelations of my childhood came when First Methodist Church got sand blasted. The work started on a Monday morning, and when we rolled up in my grandparents’ Nash Rambler with a carload of kids and a big pot of green beans for Wednesday night’s covered dish supper/prayer meeting in the fellowship hall, the old gray lady was covered with scaffolding.

On Sunday morning, we beheld a modern miracle.

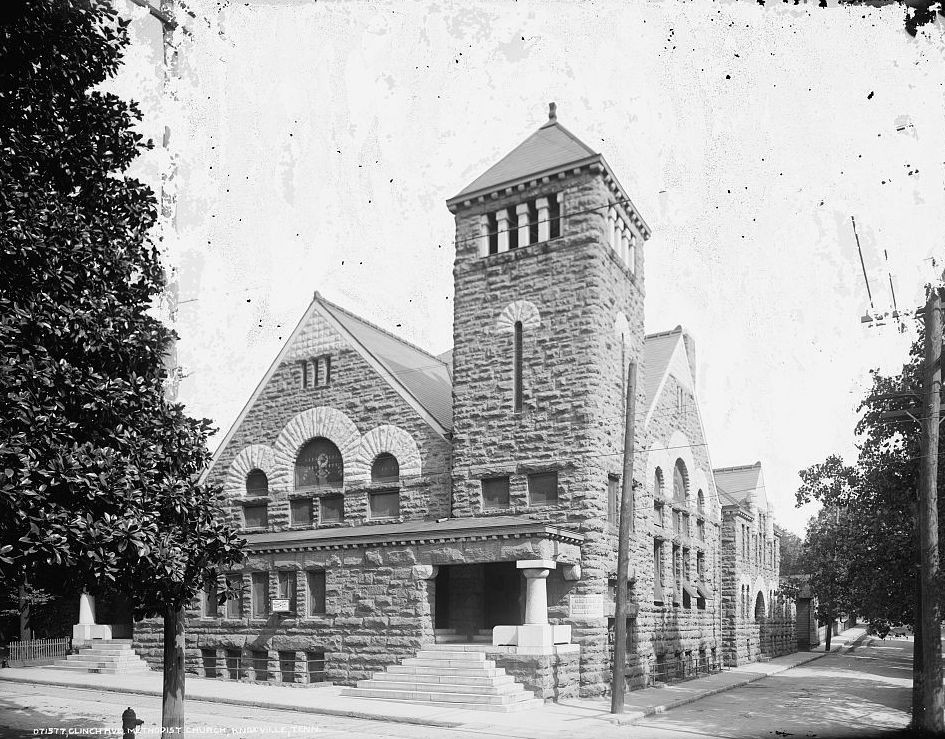

The squatty, Romanesque behemoth that had occupied the southeast side of the intersection of Locust and Clinch since 1893 was suddenly pink as a baby’s bottom. Knoxville was a coal-burning town, and, liberated from seven decades of soot that coated its Tennessee marble façade like grimy dew, First Church gleamed like those alabaster cities Granddaddy sang about. He pronounced it a wonder, a sight on earth.

First Church’s congregation was chock full of Beans from the beginning, and I’m not talking about my grandmother’s covered dish specialty. My siblings and I grew up in that old church, just like my grandfather Ralph Bean and father Albert Bean and uncles and aunts and cousins before me. I knew its crooked hallways and secret rooms by heart. Sunday mornings and Wednesday nights, my grandparents would set out from their home in Fountain City and pick up a load of other people’s children and haul us all to church. Sometimes we stopped to pick up my great-aunt Cora, who lived in a downtown apartment and was a big fan of Liberace. Her son Alfred and daughter-in-law CV sang in the choir and my smiling great-uncle Ross was always standing in the door greeting people. He and his wife, Etta, and their granddaughter Julie were regulars. Aunt Etta and my grandmother, Marion Bean, co-taught a couple of generations of Sunday School kindergartners, doling out canned orange juice and graham crackers and Jesus Loves the Little Children. The cousin inventory included Alfred and CV’s three redheaded boys.

My friends were kids I knew from cradle through high school. We had MYF socials and sleepovers and weeks at camp. My first car date was with a First Church boy who took me to see “Gone With the Wind” at the Tennessee.

First Church was my true north, even if I didn’t know it at the time. I was a child actor in the church drama club and Granddaddy, who worked at the post office and was known as the Singing Mailman for his booming baritone, was best friends with the dean of UT’s College of Agriculture. I learned more literature and history and philosophy at church than I ever did in school.

But I was sadly ignorant of First Church’s history.

The building I grew up in wasn’t the original First Church structure. The remnants of the old church stood a couple of blocks away at the southwest corner of Clinch and Market (formerly Prince Street), and was built by a bunch of Temperance Union-following Union sympathizers who had split from the Methodist Episcopal Church South over the issue of secession. It was the first Methodist Episcopal Church planted south of the Mason Dixon line after the Civil War.

I grew up knowing that my great-grandfather walked to Cumberland Gap, Kentucky, to volunteer for Lincoln’s army and avoid being drafted by the Confederates. I knew that the Beans were Republicans. But if I ever noticed the engraved marble slab that said “William Gannaway Brownlow, born August 29, 1805, and died April 29, 1876,” I didn’t have a clue who he was.

I didn’t know that Parson Brownlow was one of First Church’s founders. The fiery, defiant editor of the Knoxville Whig was jailed, threatened with trial for treason and finally exiled during the Confederate occupation. He indulged his love of bombast by adding “And Rebel Ventilator” to his newspaper’s title when he returned home after Gen. Ambrose Burnside marched in and forced the secessionist government to skedaddle.

I didn’t understand the strength of bonds forged by war, nor did I know how closely my people were attached to fellow loyalists (Confederates called loyalists Tories, Union men called Confederates Sesesh). Most of all, I didn’t understand the conflicts that lingered on after the war.

Just 18 when he took off for Cumberland Gap, John Alexander Bean was a mason and a stonecutter. When we’d drive down Broadway past Greystone on our way to town, my grandparents would tell me that he helped to build it, and the Knox County courthouse, too. He probably worked on First Church, as well.

Later I learned that Greystone belonged to Eldad Cicero Camp, a Union Army major from Ohio whose regiment carried supplies to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at the Battle of Cold Harbor. Camp stayed here after the war, read the law and made a fortune in the coal mines. In 1868, Camp killed Confederate Col. Henry Ashby in a downtown Knoxville shootout, which didn’t deter Grant from appointing him U.S. attorney in 1869 (Grant removed Camp from office two year later, allegedly for being too hard on moonshiners and the like).

It is logical to assume that Camp’s construction crew was likely composed of Union men and First Church members. The fact that Greystone stands next to the old Brownlow Elementary School (now Brownlow Lofts), named for the Parson’s son, Union Army Col. John Bell Brownlow, the developer of the Brownlow Addition just north of what is now the Fourth and Gill neighborhood, is probably no coincidence. The top floor of Greystone housed Camp’s Home for Friendless Women, and he later helped establish a local Florence Crittenden Home (legend has it that the top floor is haunted, by the way).

Former Confederates weren’t allowed to vote when Parson Brownlow got elected governor, which suited him just fine. He made himself extremely unpopular battling Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Ku Klux Klan, making Tennessee the first former Confederate state to rejoin the union and extending voting rights to former slaves. He moved on to the U.S. Senate in 1869 (senators were appointed by state legislatures in those days) and had a short, undistinguished tenure in Washington City.

William Rule

Meanwhile, another First Church founder, Union Army veteran and Brownlow protégé William Rule, became city editor of the Knoxville Whig, which Joseph Mabry bought in 1869 with the intention of turning it into a Democratic Party mouthpiece. Rule resigned and became the founding editor of the Knoxville Chronicle the following year.

When Brownlow returned to Knoxville after leaving the Senate in 1875, he went into partnership with Rule, renaming the paper the Knoxville Whig and Chronicle, which later became the Knoxville Journal. Although the scholarly Rule was nowhere near as bombastic as his mentor, he carried on the Parson’s hell-raising tradition by bashing rival editor James W. Wallace over the head with a cane on Gay Street and managing to duck when Wallace opened fire with his pistol.

Rule was elected mayor in 1873 and was a progressive who opened a waterworks, established a health department and founded a smallpox hospital. In 1914, Rule and John Bell Brownlow donated money to the Daughters of the Confederacy to erect a monument on 17th Street dedicated to the Confederate soldiers who died at the Battle of Ft. Sanders.

Despite its distinguished membership and storied history, a century after its founding, First Church’s dwindling congregation voted to abandon its downtown location and moved to a fancy new Kingston Pike address in 1966. Granddaddy Bean, by then one of the oldest members, supported the move, believing that the new location would give the church a better chance to thrive. Ten years later, we sang “How Firm a Foundation” at his funeral service in the new church’s sanctuary. Far as I know, he was the last Bean left in the congregation.

Note: Much obliged to first United Methodist Church communications specialist Lauren Robinson for providing access to the church’s extensive archives. For more information on the church born of the Civil War, see William Rule’s “Standard History of Knoxville, Tennessee (1900),” Oliver P. Temple’s “East Tennessee and the Civil War,” Noel C. Fischer’s “The War at Every Door,” and “Secessionists and other Scoundrels: Selections from Parson Brownlow’s Book,” by University of Tennessee historian Stephen V. Ash (if you can find it).