Have I mentioned that I’ve moved?

And yeah, I’m just kidding – I realize that I’ve spoken (or written) about little else this whole summer long, getting way behind on most anything that doesn’t involve wrapping stuff in newspaper or making trips to the recycling center, so naturally I haven’t had time to keep up with current events.

I haven’t seen Oppenheimer yet, but I will, soon as I find my shoes. As a kid who grew up wearing dog tags so my body could be identified when the Russians decided to blow up Fountain City Elementary School, how could I not be interested in this film? I can’t remember a time when I didn’t worry about mushroom clouds. I didn’t have a clue who Oppenheimer was beyond being the Father of the A-bomb, but the name is a marker of those scary times.

As time passed, I started hearing about nuclear energy as a positive thing – Atoms for Peace, nuclear power plants, X-ray technology, cures for cancer. It was all way over my head, but it sounded like we were seeing something good come from an awful thing.

Another thing I remember hearing about during those days was Hodgkin’s Disease. It was scary, the way it seemed to pick out the brightest, most athletic young men and take them away from us. The first time that struck me was when I heard about Johnny Payne, the outstanding Central High School quarterback who seemed to have it all – talent, brains, winning personality – until Hodgkin’s Disease took him down.

I was in my early 20s and living in Charlotte when my brother John was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Disease. I remember Daddy calling to give me the bad news, and it quite literally knocked me off my feet – I suddenly found myself sitting on the kitchen floor beneath the wall phone, receiver in my hand, listening to Daddy going on about how John was tough and smart and strong enough to beat the thing. All I could think was, “So was Johnny Payne.”

We went home for a visit and Daddy was upbeat. He said John’s doctor told him, “We’re going for a cure.”

I was afraid to believe it.

A few weeks later, John’s favorite band, Blood, Sweat & Tears, came to Charlotte for a one-night show, and he got his doctor’s permission to fly over the mountains to go see them with us. I was shocked by his appearance. Strong, muscular, athletic, laugh-a-minute Johnny looked like we’d just busted him out of a concentration camp. Wafer-thin, voice reduced to a whisper by his blistered throat, he hung in there bravely, but the band was a no-show, and we decided to drive him back home.

It was a sad, scary time, but we all hung onto the “Going for a cure” promise.

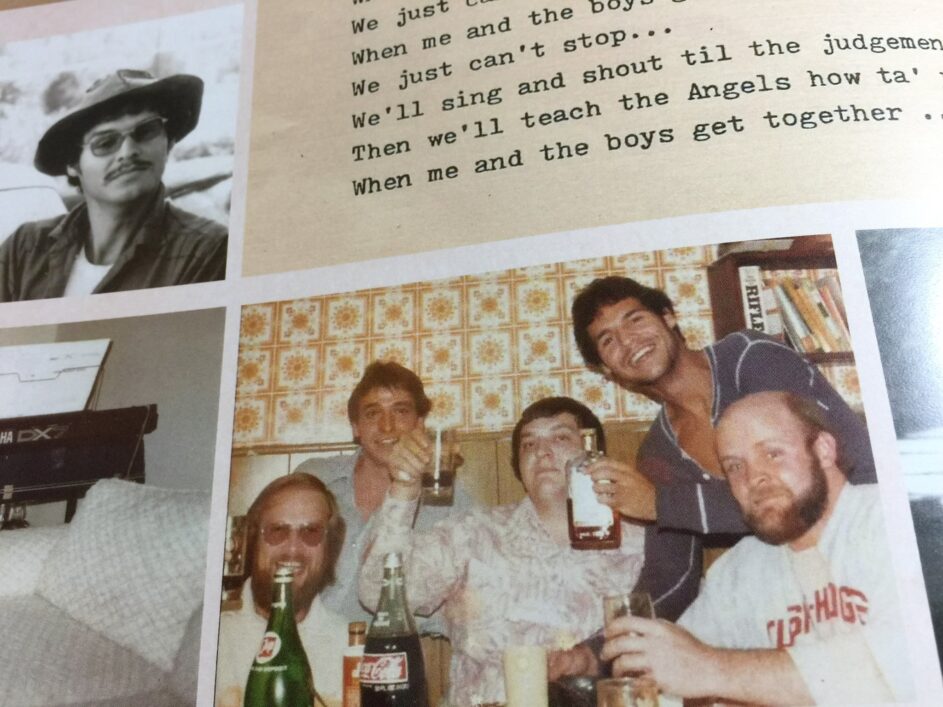

He toughed it out and finished the course of treatment. He was weak and skinny, but slowly improved, and gradually got back to his old ways – playing music, pulling “fast ones” (which he frequently caught on tape) and charming almost everyone he ever met.

Most anyone who knows me knows the rest of this story. He never got well, and the rest of his life was a struggle with the effects of radiation damage to his heart and his lungs until he died of respiratory failure on August 18, 1984, at the age of 33.

I write about him every year at this time – mostly funny stories about his pranks, his music and those tapes that have gone around the world. I feel certain that nobody who knew him will ever forget him, and that he kept making friends long after he was no longer here.

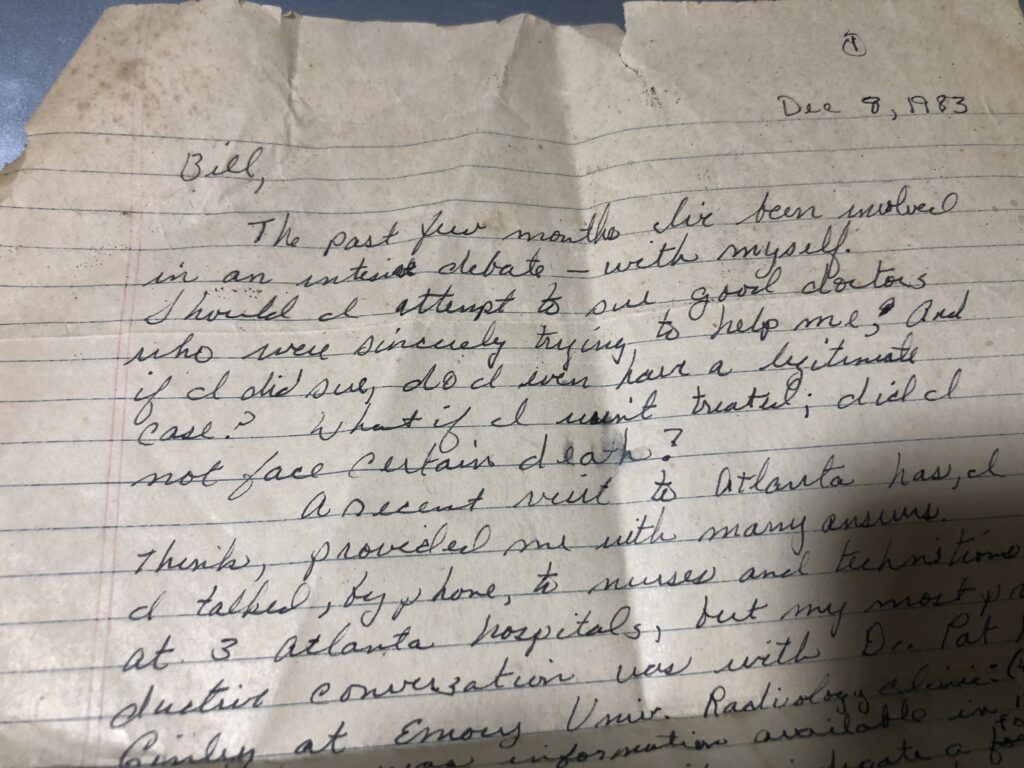

This year, in the course of cleaning out my desk, I came across a new artifact. It’s a first draft of a letter he was writing to his doctor, who’d been a young resident at UT Medical Center when John first took ill. Here’s how it begins:

First draft of John Bean’s letter to Bill Robinson

“Bill,

“The past few months I’ve been involved in an intense debate – with myself. Should I attempt to sue good doctors who were sincerely trying to help me? And if I did sue, do I even have a legitimate case? What if I hadn’t been treated; did I not face certain death?

“A recent trip to Atlanta has, I think, provided me with many answers…”

Bill Robinson was the one who finally accurately diagnosed John’s illness (it always seemed peculiar to me that the radiologists who had originally treated him were so baffled by his symptoms a decade later, but that’s perhaps another story), but John and Bill became the closest of friends, and in the end, Bill was with him when he died.

This letter is dated December 8, 1983 – eight months before John’s death – and it is a painful account of his struggle to understand what had happened to him.

He had done a lot of research and found the closest available expert in the field of radiation damage – a radiologist at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta – and paid him visit, under false pretenses, of course. He’d gotten hold of his own medical records (after hiring a lawyer and spending vast amounts of time, struggle and money) and introduced himself as a graduate student researching the aftereffects of a nuclear war (a popular topic at the time because a recent TV show about nuclear winter had smashed viewership records).

The doctor was quite obliging and was shocked by what he saw. He predicted a grim and brief future for the patient whose records he examined and was stunned by the level of radiation exposure involved.

The visit shook John, although if it made him lose hope, he never let on. Over those last months of his life, he was in and out of various hospitals, losing lung function but making new friends everywhere he went. One of his last fast ones was to tell his favorite orderly he was going to break out of the hospital and go “as far as this (oxygen) tank’ll take me.”

The orderly went running out to the nurses’ station to warn them that Bean was making a break for it, which suited John just fine. Laughter beats tears every time.

Betty Bean writes a Thursday opinion column for KnoxTNToday.com.