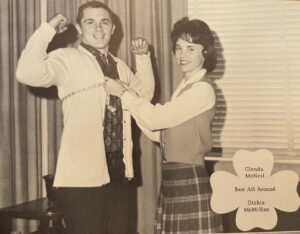

Dick McMillan didn’t think too much of it when a guidance counselor encouraged him to fill out an application for the Federal Bureau of Investigation during his senior year in high school. Back then, he and his high school sweetheart/wife of 61 years, Glenda McNeil, were together voted Best All Around for the Central Bobcat class of 1962.

By the summer after graduation, he’d pretty much forgotten all about sending in that application. Until he got a phone call in late August telling him he’d been accepted, pending a background check and other protocols necessary to start working for the F.B.I.

Dick McMillan and Glenda McNeil in the Central High School annual from 1962.

So, in September, he moved to Washington, D.C., found some roommates and started work – in the mailroom.

“That’s where everyone started,” McMillan said, referring to the new class of recruits who came in to handle clerical duties. Meanwhile, Glenda was settling into co-ed life at East Tennessee State University.

All the new workers had a day to meet, however briefly, the agency’s long serving and controversial director, J. Edgar Hoover. Dick recalled going to the office and being greeted by Hoover’s second in command, associate director Clyde Tolson.

“I really liked Tolson, honestly. I only met Hoover that one time,” he said, adding that Tolson directed him to grab a tissue and wipe his hands before going in to greet the Big Kahuna. “Apparently Hoover really disliked touching sweaty palms.”

He wasn’t settled into D.C. for very long, when the miles between them were becoming too much for Glenda – “I told him I wanted to get married.” And marry they did, in November that same year, in her parents’ house, where she and Dick now live.

Prior to their wedding day, Dick had smartly secured a furnished apartment for his new bride’s arrival, and the two teenagers from Fountain City (he was 19, she was 18) settled into their new life together in our nation’s capital. They weren’t there long before Glenda decided she needed to find a job. Knowing no one but her husband, one day she took the bus into central D.C., straight to the Library of Congress.

“It seems no matter where I was going, or what I was doing, I always found the guardian angels. Or they found me,” Glenda said. “There was always someone there to help me.”

Glenda and Dick McMillan on their wedding day in November 1962.

In this case, it was the bus driver who told her where to go and who to talk to about a job. Her brilliant tying skills (110 words per minute) got her hired in short order at the library. She fairly quickly moved into a management position, and for a time, rare for that era, was making more money than her husband. She was making $72.50 a week to his $70.50, in today’s money a bit over $700 a week for each of them. Not too shabby.

In due time, Dick decided he wanted to pursue becoming an agent. Back then, agents had to hold either a law degree or an accounting degree. Georgetown University was out of the question financially. So, the McMillans moved to Hyattsville, Maryland, to establish residency where he could get in-state tuition to attend the University of Maryland while still living close enough to D.C. for both of their jobs.

But, not long after their first anniversary came one of the worst days in American history. Though it has been 60 years now, they both wince at the memory, as does anyone who can answer the question: where were you when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated?

It was Friday, November 22, 1963. Dick was en route between offices waiting for an elevator when the doors opened and a woman emerged in a not quite right state of mind. After trying repeatedly to get her to tell him what was wrong, she finally blurted out through tears “the president’s been killed.” No long after, he was ordered to vacate the building for the rest of the day. He tried calling Glenda’s office to let her know he was walking over to meet her. The phones weren’t working.

“I went outside, and it was basically pandemonium. People were running everywhere,” Dick said. “We didn’t know. Was it just an attack on the President, or was something bigger going on?”

He reached the Library of Congress, but couldn’t find his wife. Turns out she had already left her building and was out looking for him. They eventually found each other and made their way home.

The next day was a chilly, foggy, rainy day in D.C. The McMillans decided to drive into the city as Kennedy’s body lay in state at the White House. “People were walking around like zombies,” Dick said. “Everyone was just in shock.”

Black Jack, the riderless horse in J.F.K.’s funeral procession (Photo credit: White House Historical Association).

By Sunday, J.F.K. had been moved to the Capitol Rotunda. Dick and Glenda went into the city again, and considered paying their respects to the slain president. The line stretched for two miles in freezing temperatures. Though the rotunda was scheduled to be closed at 9 p.m. it remained open through the night as an estimated 250,000 mourners filed through.

On Monday, Nov. 25, they found a spot in Lafayette Square by the White House to watch J.F.K.’s funeral. The procession traveled from the Capitol building up Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, then to St. Matthew’s Catholic Cathedral and on to Arlington Cemetery. They both particularly noted the presence of French President Charles de Gaulle as well as Ethiopian dictator Haile Selassie. The memory that really gets to Dick, though, is that of Black Jack, the riderless horse with boots turned backward following the horse drawn caisson bearing J.F.K. to his final resting place.

It was the assassination that warranted a good deal of the conspiracy theories surrounding it, yet birthed thousands in the years since that really don’t. It is a wound from which this country has never healed. Dick wasn’t an agent. As a clerk he wasn’t privy to the highest levels of intelligence in the bureau where he worked. He simply said that what he did run across relative to the killing of J.F.K. leads him to believe the mafia was behind it, if not solely responsible for it, that Oswald was “a” shooter but not the only one, and that the “magic bullet” theory is a load of bunk.

He also doesn’t hold the Warren Commission report in high regard, nor his former boss, Hoover, who has been credibly accused of misleading the commission. In a declassified memo released in 2017, in the aftermath of Lee Harvey Oswald’s extrajudicial murder by Jack Ruby, Hoover said “the thing I am concerned about … is having something issued so we can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassin.” Make of that what you will.

By the time 1964 rolled around, the young couple decided they wanted to start a family, and it was time to move back home to Fountain City. Dick went on to a long career with the Knoxville News Sentinel.

Beth Kinnane writes a history feature for KnoxTNToday.com. It’s published each Tuesday and is one of our best-read features.