Much has been said and written of the strong-willed and strong-minded women of early East Tennessee. As such was Cynthia Elvira Gambill Smith (1819-1904).

Cynthia was accustomed to a good life. She and her husband, James Monroe Smith, were living on their plantation, where Admiral David Farragut had been born. But the year 1861 brought sudden changes. Her husband and two of their sons were away fighting in the Civil War for the Confederate Army. She was left at home to care for seven children and all that was to be done with running a farm.

Cynthia Smith

By July 1862, she had lost her two youngest daughters to cholera. This had to be devastating as her husband came home just long enough to see that the children were buried and then returned to the war.

By November 1863, the Union Army had entered Knoxville. Cynthia had laid up a supply of food and Confederate money, which she stored in a cellar built with a trap door covered by carpet. She had stored meat by hanging it in an upstairs room, and the windows were covered to keep out the light.

When the Union soldiers came to plunder and steal, Cynthia positioned herself over the trap door so as to hide any evidence of the goods that lay below her. As the soldiers began to climb the stairs to look around, she bade them an unwavering eye and said, “Go ahead, there is nothing up there.” Because the upstairs was dark, the soldiers – fearing an ambush – decided not to look further. They did, however, take all of her chickens and livestock except one old horse that was blind.

Bent on revenge, Cynthia devised a plan. She took all of her carpets and made blankets. Further, she took all her linens and made bandages of them and turned feather beds into pillows. She then loaded her supplies into a wagon and, hitching the old blind horse, she and her helpmate, Mary Marley, and Cynthia’s young son James Polk, set out to deliver them. She stealthily made it through the Union lines to the Confederate hospital but was stopped by soldiers on the way home.

Hastily, she had her young son hide under Mary Marley’s hoop skirt, where he went undetected. Mary was allowed to return home, but Cynthia was taken captive and held until the siege of Knoxville was over.

During her captivity, she became friends with the guards and joked and played cards with them. The story goes that a woman Union sympathizer came for the purpose of seeing what a rebel looked like. Quick-acting Cynthia kicked her down the stairs and explained that she was only protecting what was rightfully hers.

As if nothing else could go wrong, the oldest son left home in 1864 to fight for the Union cause and remained there until after the end of the war.

When the Civil War was over, Cynthia was penniless, her Confederate money worthless and her plantation in ruins. Her property was being confiscated because of alleged disloyalty even though she and her husband had taken the Oath of Allegiance to the Union.

Her husband was still out of state because of threats against his life should he return home.

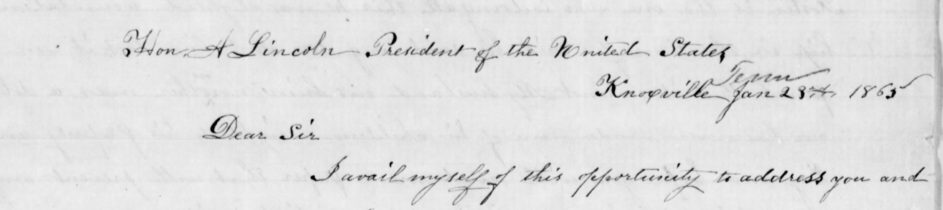

Documentation of the referred letter (From the National Archives)

In a desperate cry for help, Cynthia sent a letter on Feb. 28, 1865, to President Abraham Lincoln asking for protection and to save her land. Apparently, Lincoln never saw the letter as the documents state it was referred to Major General “Slow Trot” Thomas and no action was taken. Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865.

By July of that year, her husband had returned home and been fatally shot. Cynthia lived another lonely 39 years and was buried beside her husband in Concord Masonic Cemetery.

A special thank you to the late Beulah Lee Smith Prater Pratt, Cynthia’s granddaughter, for a glimpse into Cynthia’s life in her book “I Remember Granny.”

Cynthia Smith’s closing (From the National Archives)