Note: Previous story on this topic here.

From the beginning, Amy Mays Emert took extra care of the three nameless infants. After a while, she decided the least she could do was name them, so Infant Boy Lonas became Jack, because she pictured him as a crackerjack; Infant Girl Gilson became Sissy because she was smack in the middle of a pack of six brothers and six sisters; and Infant Boy Walker became Buddy because it felt right.

“I paid extra attention to their graves, because they were the only proof that these children ever existed, and I didn’t want them to be forever nameless,” Emert said.

Emert is a member of Friends of Cavett Station, official caretakers of the historic Mars Hill Cemetery, originally a committee of the Cavett Station Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Emert is the historian for both organizations and an active member of the work crew that has spent years cleaning up the cemetery.

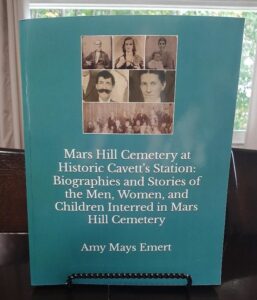

Now she has written a book about the families connected to the cemetery, and anyone with an interest in local history or genealogy – particularly those who have kinfolks named Cavett, Lones (or Lonas), Kidd, Parham, Walker, Craig, Covington, Roberts or Wittenbarger – will want to take a look at Mars Hill Cemetery at Historic Cavett’s Station: Biographies and Stories of the Men, Women and Children Interred in Mars Hill Cemetery, by Amy Mays Emert. This book tells the stories of as many of those who are buried in the old cemetery at Cavett Station as Emert could find. It was a labor of love for the Knoxville native who is a professional genealogist, a student of local history and a descendant of Tennessee pioneers.

Here’s what she posted on her Facebook page when she announced the publication:

“After three long years of research and writing, my book about the men, women and children buried in Mars Hill Cemetery has been published! It is 407 pages long, and includes over 345 images and documents. I am so proud of this book, and I am so blessed that God directed my path to ‘meet’ all of the people whose stories I have gotten to tell.

“The couple in the middle of the picture collage are Archimedes Tate Craig and Mary Rush Parsons Craig, my great-great-grandparents. For those of you who knew my Nanny, they were her parents. You need a majestic name like Archimedes to get away with having that mighty moustache.”

Although Emert agrees with other historians who have researched the tragic history of Cavett’s Station that Susanna Cavett was the first to be buried there, there is uncertainty as to whether she was the mother of Alexander Cavett, who built the blockhouse about eight miles west of James White’s Fort, or his wife. Both were named Susanna. “Susanna Cavett’s was the first body buried in the Mars Hill Cemetery, but nobody knows the name of his wife, or any of his children except for Alexander Junior. Virginia marriage records are very difficult to sort out. My first instinct is to say, yes, that’s his mother, but we’ll never be completely certain.”

All we do know for sure is that she was joined about a year later by the rest of her family, all but one of whom were massacred in September 1793 by a Cherokee war party that had intended to attack the city of Knoxville, but had settled for the blockhouse after they’d gotten behind schedule and been spooked by the sound of White’s Fort’s cannon fire greeting the dawn. Led by the unusually violent Chief Doublehead, the braves decided to take out their frustrations on Alexander Cavett’s blockhouse. We know that Alexander Cavett Jr., a toddler at the time of the massacre, was the only survivor, but he was murdered soon after his capture, probably in Alabama.

Another thing that bothers Emert about the cemetery’s history is how little is known about Alexander Cavett, who was 48 when he was killed.

“He had made quite a name for himself before he came here,” she said. “There was far more to him than just the way he died, which was heroic, but he was also a hero long before then. In 48 years, he had led a very productive life, and that’s what I want people to know.”

Unfortunately, a lack of knowledge about our history is pretty typical for most folks, Emert said.

“I went to high school at West, and I never even heard of Cavett’s Station. They barely taught us history, much less Tennessee history. They’ll put kids on a bus for a field trip, but I had no idea who James White was. At this rate, we’re going to lose all of that. And then the next generation won’t know it, and it will be forgotten.”

Nobody knows exactly how many are buried at Mars Hill Cemetery, but Mays and other researchers have found that far more – up to 500 – than originally believed, and their numbers include veterans of later military conflicts, including the Civil War.

For more information about historic Cavett’s Station, or to purchase the book, email Amy Mays Emert here.

Cousin Amy

Not long ago, Amy Emert and I discovered that we are cousins.

Her three-times great grandfather, William Camp Bean, and my great-great grandfather, Henry A. Bean, were brothers – sons of Sarah Camp Bean and John Bean, a veteran of the War of 1812 and a grandson of Tennessee’s first permanent settlers, William (a veteran of the Battle of King’s Mountain and the Cherokee Wars) and Lydia Russell Bean (who was captured by the Cherokee and saved from being burned at the stake by Cherokee Beloved Woman Nancy Ward).

Since he had no recorded middle name, we have dubbed our mutual great-grandfather John of Ebenezer to distinguish him from all the other Johns in the family, who are numerous. We figure he is probably the granddaddy of all the Bean offspring in the Knoxville area, who are also numerous.

William Camp Bean was in his early 30s, married with a houseful of children when he followed his older brother Henry A. Bean (my great-great-grandfather) and his nephew John Alexander Bean (my great-grandfather) into the Union army after the Confederacy stepped up efforts to beef up its troops by drafting men from East Tennessee. They were all mustered in in Kentucky after walking to Cumberland Gap.

Henry served for a year before falling ill with scurvy, losing most of his teeth and part of his jawbone before being given a medical discharge. Hs younger son, George, replaced him. John served until the end of the war and was discharged in April 1865. He would have sons who fought in the Spanish-American War and World War I. He is buried at Bookwalter Cemetery in Inskip. William is buried in a veterans’ cemetery in Nashville.

Betty Bean writes an opinion column each Thursday for Knox TN Today.