There’s a very interesting exhibition of the paintings by Knoxville-based artist Barry Spann at the District Gallery in Bearden. It’s the first local exhibition in more than a decade.

Those who remember Spann’s work likely know the exquisite set of collotypes, “Twenty-Seven Landscapes,” published at Trianon Press in Paris, partly by Arnold Fawcus, Trianon’s founder and director, and partly by Spann, who finished the work when Fawcus died before the printing was complete. Copies of the book, The Pursuit of Happy Results, written by Spann’s wife, opera librettist Emily Anderson, that documents the entire process, are for sale at the gallery.

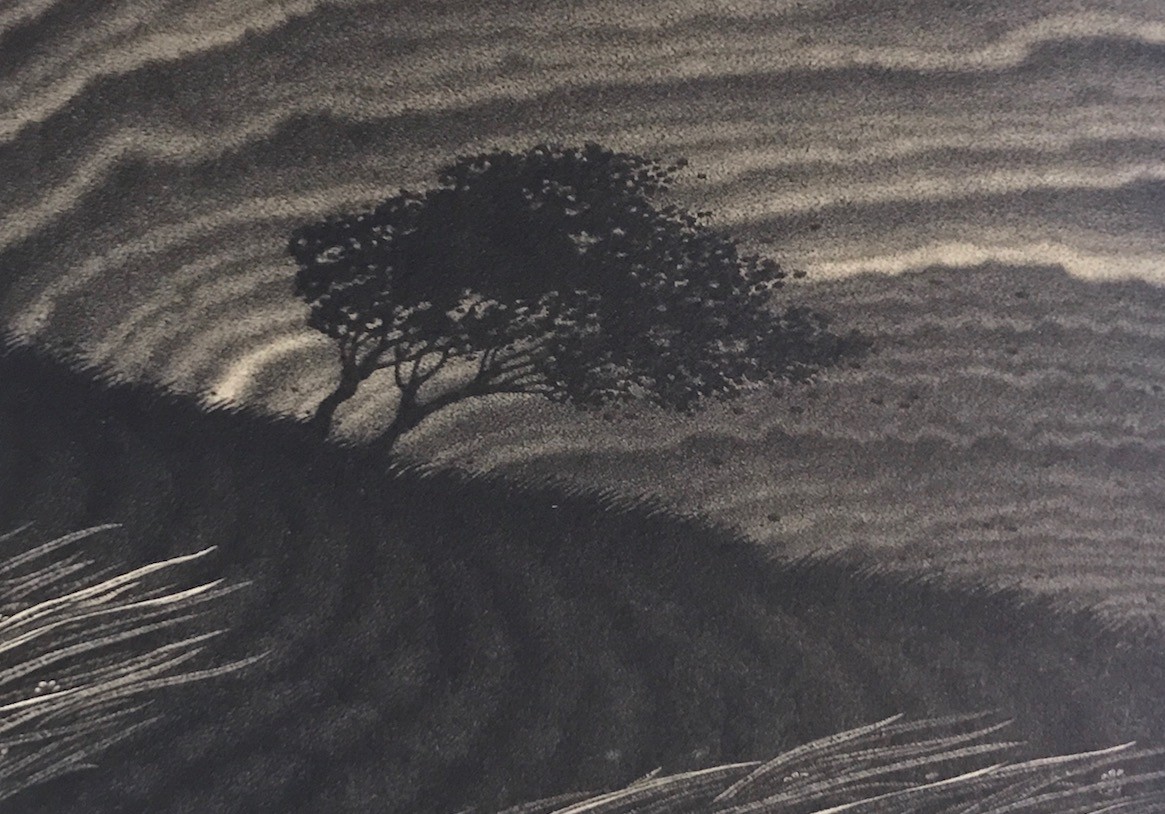

Barry Spann, Dusk, 1977, Collotype

In the late 1980s, Spann painted a series of canvasses for the dining room at Whittle Communications’ new headquarters across from the historic Knox County Courthouse. It’s now the Federal Courthouse. The paintings’ sensibility references Chinese brush paintings. They still hang there.

Barry Spann, Multi-panel painting, Federal Courthouse, Knoxville, Tennessee.

More recently, Spann painted a series of backdrops for operas written by Anderson, including the opera “Ashes” that premiered in Paris, then moved to Beijing.

One of the fascinating dimensions of all of these images is how much the movement in Spann’s work reflects the developments in contemporary classical music, an association which Spann seemed to know nothing about.

It’s actually not uncommon for paths in different art forms, painting, sculpture and music, to move in proximity, with the practitioners of each only peripherally aware of each other. It’s happened for centuries. Attribute it to the arts gods.

While he works, Spann’s personal listening tastes lean toward 18th century Baroque music. One can see associations between the note patterns in the music of Bach, Vivaldi and Scarlatti, for instance, and the tightly aligned hatch lines in the “Twenty-Seven Landscapes,” clearly seen in “Dusk,” from 1977.

The modern movement of minimalism in classical music includes the best-known composers in contemporary classical music: Americans Philip Glass, Steve Reich, John Adams and Terry Riley; Estonian Arvo Part; Brits Michael Nyman and Gavin Bryars; Dutch Louis Andriessen; and Polish Henryk Gorecki.

Minimalism featured tight, repeated patterns that slowly evolved. A kind of neo-baroque. Then came post-minimalism. That has now transformed into “totalism,” which reduced the number notes in the pattern and stretched out the sounds. Everything that isn’t absolutely necessary is eliminated. Changes are almost imperceptible. John Luther Adams’ 2014 Pulitzer Prize-winning Become Ocean is a remarkable example. The Pulitzer committee described the perfect palindrome as “a haunting orchestral work that suggests a relentless tidal surge, evoking thoughts of melting polar ice and rising sea levels.”

That’s where music reconnects with the Spann’s Twenty-One Still Lifes in the current District Gallery show. All of the busy lines in Spann’s early collotypes are gone, so are the layers of alternating light and dark waves in the Whittle mountain paintings.

Barry Spann, Still Life with Flower and Star, oil on canvas, 2017

Everything that isn’t absolutely essential to the story in the image has been pushed out of the picture plane, including color density and even parts of the image elements themselves.

What is left is almost primal, fundamental information. Thin line drawing, pale washes of color, just enough to distinguish surfaces, even the edges of shapes disappearing. Parts of the main subjects, such as the blossom on the end of stem in Still Life with Flower and Star are outside the picture plane.

The result is a meditative, calm, peace-and-quiet throughout the range of images throughout the show. The elements differ from one painting to another. The color changes, say the difference in the same pink in sunlight and shadow, but the overall sensibility remains.

Long before there was modern art, the Greek philosopher Aristotle said that “the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.”

In fundamental ways, although the image production and drawing techniques in Spann’s work have changed in 40 years, Twenty-One Still Lifes has an emotional bond to Twenty-Seven landscapes.

They’re Barry Spann, full circle.